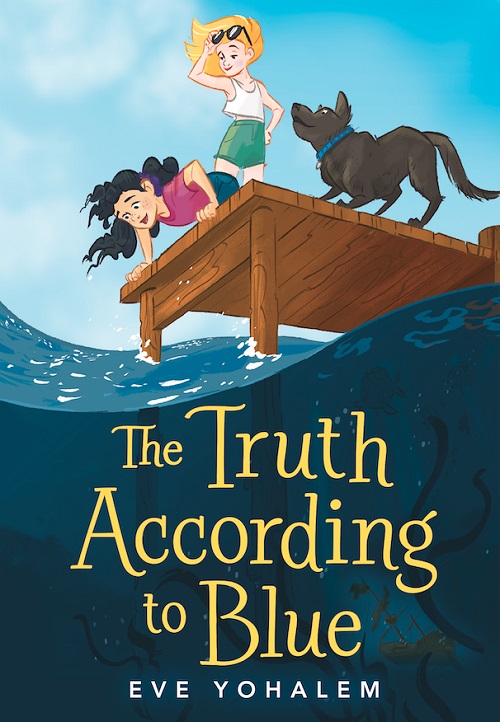

Eve Yohalem is an acclaimed author who has published several novels. Her most recent, The Truth According to Blue, published by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, focuses on the adventures of a 13-year-old girl determined to find a sunken gold treasure—a treasure that she believes, is her family’s long-lost fortune.

This heroine, nicknamed “Blue,” also happens to live with type 1 diabetes (T1D).

To get a handle on what it is like to grow up with T1D, Eve naturally turned to kids who live with T1D today. But she also turned to another source: Her sister, Jennifer who has lived with T1D since she was nearly 13-years-old.

In recognition of National Diabetes Awareness Month, we asked Eve to interview Jennifer about growing up with T1D and discuss why works of fiction like The Truth According to Blue are critical to increasing awareness and understanding of life with T1D.

Eve: Tell me the story of when you were diagnosed.

Jennifer: In the summer of 1975, just before I turned 13, I got a very bad stomach virus at camp. I didn’t eat for probably three days. I remember standing in line to go eat and not being able to stand long enough before getting nauseous. Anyway, I was sick a lot that summer and lost a lot of weight. I got home end of August and I was thirsty all the time and peeing all the time.

Eve: Classic.

Jennifer: Finally, very end of September, we went to the pediatrician’s office, and she took blood. I’d had to fast beforehand, and I was hungry. So after the blood test, we went to a diner, and I had a big plate of pancakes with real maple syrup.

Eve: Perfect.

Jennifer: The next day we got the test results. The doctor said, “You have diabetes. You have to go into the hospital.”

Eve: Do you happen to remember what your fasting glucose was?

Jennifer: Yes. 364, which is not horrific.

Eve: Can you imagine what it was a couple of hours after the pancakes?

Jennifer: Oh my God. I can’t.

Eve: What was diabetes treatment like when you were diagnosed?

Jennifer: There were no blood glucose meters. You would test your urine with a dipstick or dissolving tablets, but it wasn’t precise. There was no way to know exactly what your blood sugar was. You just guessed by how you felt. Once a day you took a set amount of long-acting insulin, and then you would take a set amount of short-acting for each meal. You were almost guaranteed to have side effects.

I left the hospital with insulin dosages and a meal plan that I had to stick to no matter how hungry I was or wasn’t, and that was all I knew. No one ever explained anything to me. No one told me, “This is what diabetes is about. This is why your body is reacting this way.” It was a month after I’d turned 13.

Before I was diagnosed, I might eat two or three chicken drumsticks at dinner. After I was diagnosed, my meal plan said I could have one drumstick at dinner, and then right before bed I had to eat a sandwich and fruit–a whole extra meal. I hated it. I was told, “Well, this is what the doctor said to do, so this is what you have to do.” Finally, one night I threw a tantrum. I said, “I want another chicken drumstick. I’m still hungry from dinner. And I hate those snacks.” Finally, Mom and Dad called the doctor who said I could have more chicken at dinner.

You had in your list of questions, “What would you like say to your younger self?” I would say, “Ask questions.”

Eve: Did you know any other kids who had diabetes?

Eve: Did you know any other kids who had diabetes?

Jennifer: I never met another person with diabetes while I was growing up. It was a silent disease. Nobody talked about it. Nobody knew much about it.

Eve: What was it like for you being the only kid you knew with diabetes?

Jennifer: The kids knew that sometimes I would have to eat candy, and I would go to the nurse before meals because I would have to check my urine and get a shot. But nobody had any idea what it was about, including me. I didn’t know any other people who were dealing with this or how to find them. It was just all my problem.

Eve: When I was doing research for The Truth According to Blue, I talked to a bunch of kids who have type 1 diabetes. One of them told me that the thing she hates most about dealing with it is changing her pump site, which is a detail I borrowed for Blue. What’s the thing you hate the most?

Jennifer: Well, I think the scariest thing is that you can’t get pump supplies and continuous glucose monitor supplies just anywhere. You can only get them from suppliers. If you run out, or you forget to bring supplies with you, you can’t get what you need. And if you can’t get your stuff, what do you do? If I’m at work and it’s 9 at night, and the doctors’ offices are closed, even if I go to an emergency room, they don’t have what I need. If I travel across the world, I have to know that I can get what I need there. That’s the scariest thing.

As a kid, I would say the hardest part about diabetes was I always had to check my urine twice before I could eat, which could take 5 or 10 minutes. I could be ravenously hungry or my blood sugar could be low, but I had to wait. Putting off satisfaction is really hard for me now because I constantly had to put off my needs while I was growing up.

Eve: Were there any books about kids who have diabetes when you were a kid?

Eve: Were there any books about kids who have diabetes when you were a kid?

Jennifer: No, none. There was nothing about diabetes anywhere. There was no internet. You had to ask your doctor, and I didn’t have an endocrinologist. I had a pediatrician. I don’t even know if there were pediatric endocrinologists back then.

Doctors didn’t give out a lot of information then. Nowadays, there are communities, there are chatrooms, there’s Breakthrough T1D. It’s super, super important to get to know other people with diabetes. You learn so much that way.

Eve: I thought you told me there was one really cheesy novel.

Jennifer: That was Don’t Call Me Sugar Baby. I think I was in college when it came out.

Eve: That’s a hilarious title.

Jennifer: That was it, as far as I know. There was nothing nonfiction let alone fiction. Fiction is so key.

Eve: Why? What can fiction do that nonfiction can’t?

Jennifer: Fiction will let you get to know a person as another human being, someone you feel empathy for, someone you care about, someone you like and want good things for. It’s like having a friend. Nonfiction will just give you facts. It’s very different from getting information in fiction where you just absorb it because you care about someone. It’s huge.

Eve: When I told you I was writing a book about a kid with T1D, what was your reaction?

Jennifer: I was so excited. First of all, there still are very few books out there with kids who have diabetes. There are a bunch of books about kids with cancer, but there aren’t a lot of books about kids with other medical conditions.

What you were doing was making diabetes a normal part of humanity, where kids would look at someone with diabetes and think, “Oh, that kid’s just like me.” And “Oh, I know about diabetes now. It’s really tough.” Or “Hey, I want to get to know that person. She’s really brave.” It’s normalizing something that’s never been treated as normal and bringing attention to something that hundreds of thousands of children live with but nobody ever talks about.

Eve: One of the things that really surprised me about The Truth According to Blue was how many adult readers I heard from who have diabetes. They wanted to buy this book for kids in their families, for example, so that the kids would understand what their lives were like. I didn’t anticipate that. I wrote it hoping kids with diabetes would read it, but it didn’t occur to me that it might be meaningful to adults who have diabetes too.

Jennifer: That’s wonderful.

Eve: How did you feel when you read the early draft that I showed you?

Jennifer: I loved that you did this. I knew there was a part of you that did at least a little bit of it for me. I loved that you were putting diabetes in the world for the younger generation. The best thing was that you were writing a great story about friendship and adventure. The main character happens to be diabetic, but that’s not what the story is about. You were bringing out information about diabetes, but in a really matter of fact way. It was extraordinary to me. This was a wonderful, intelligent story that was interesting and fun and exciting, and it featured diabetes. But it wasn’t a pity party.

Eve: I really didn’t want it to be a pity party.

What do you wish that people without diabetes knew about people with diabetes?

Jennifer: That it doesn’t change who we are, and it doesn’t change what we can do. Your book shows that from the inside and the outside.