Scientists worldwide are attempting to determine why some people predisposed to type 1 diabetes (T1D) eventually end up developing the disease. There is a genetic component involved, but that alone will not provide an answer for the 64,000 people who develop T1D in the United States each year, who, for the most part, lack any of the genes that make them susceptible. So experts are focused on many different kinds of environmental factors that may be potential triggers. One of the most promising leads is the viral hypothesis, which posits that viral infections, particularly those from the enterovirus group, may be partly responsible for creating the conditions and environment in the pancreas that eventually leads to T1D.

That’s why researchers, many of whom have been funded by Breakthrough T1D, including some associated with the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes Viral Working Group (nPOD-V), recently published their rationale for the creation of a vaccine that could prevent some of the population of people who are susceptible to T1D from actually developing it. The paper, in the journal Diabetologia, focuses on a group a viruses called enteroviruses.

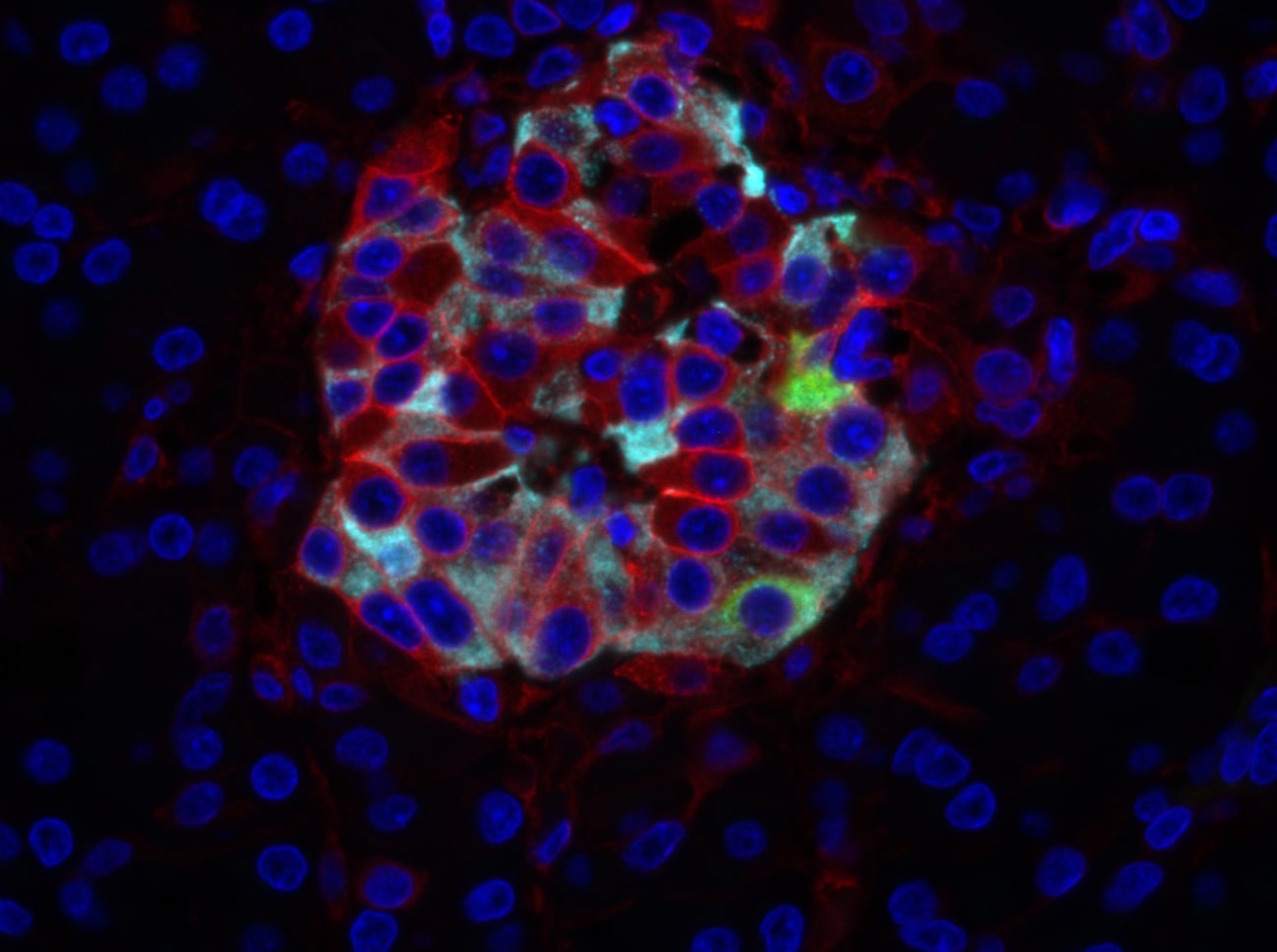

The reason that enteroviruses are in the spotlight is because a protein linked with some of these viruses has been found in all pancreatic samples being studied in association with T1D. The main enterovirus culprits seem to be from a class called coxsackieviruses, specifically coxsackievirus B (CVB). Alberto Pugliese, M.D., an investigator at the University of Miami’s Diabetes Research institute, the executive co-director of Breakthrough T1D’s nPOD and an author on the paper, says that creating the vaccine to address CVB is critical. “Within this family there are six main variants, and a vaccine could be designed that could protect from at least five of these variants, especially the ones associated with T1D risk,” says Pugliese.

Such a vaccine could keep a large part of the population from developing T1D, because many individuals with type 1 diabetes have shown evidence of an enterovirus infection. However, the impact of CVB, or any other virus by itself, cannot completely explain the occurrence of T1D, as this is not the lone cause of the problem. Many researchers believe that chronic infections could put the immune system in a constant state of reaction, causing inflammation and stress for beta cells. Jessica Dunne, Ph.D., director of the prevention research program at Breakthrough T1D and a lead author on the paper, says host-virus interactions may indeed hold the key to understanding why T1D develops at different timescales for different people. “The host immune system is reacting to the virus, and one possibility is that the ongoing immune response may be causing damage to the beta cell,” says Dunne.

The Breakthrough T1D T1D Fund has invested in Provention, a company that will develop a vaccine for enteroviruses for T1D. Sarah Richardson, Ph.D., a Breakthrough T1D career development fellow, an investigator at the University of Exeter Medical School and an author on the paper, says that “the only way to prove the involvement of these viruses definitively is to perform clinical enteroviral vaccine or anti-viral trials in individuals either at-risk of developing type 1 diabetes, or soon after onset, and show that these can prevent or slow progression of the disease.”

The vaccine may also help reduce the manifestation of other conditions associated with enteroviruses. It could help people avoid or lessen the impact of heart muscle inflammation, brain and brain stem membrane inflammation, and hand, foot, and mouth disease. Most of those conditions are more prevalent in the general population than T1D.

You can read more on our plans to make T1D preventable by going here.